Moon Kite of the Diamantina

Introduction

In 1991 I took a sabbatical leave to the Univ. of Queensland in Australia to work in the laboratory of Dr. Jack Pettigrew, a noted visual physiologist. While my own research was mostly on studies of the auditory system, I had also done some work in vision. Likewise, Jack also had a few papers focused on audition so we shared many common interests. But one of the other reasons I had picked this lab was that Jack was famous for doing interesting biological field studies in remote areas on interesting fauna. Since I went into biology at a late stage in my career (as a third year graduate student, I took Zoology 106 with mostly other freshmen at the Univ. of Michigan because I had not had any biology course since 9th grade), I was always fascinated by field studies and curious as to what they were like. So shortly after I arrived in Brisbane, I told Jack that I would be interested in participating in any field work, if he had ongoing studies. Well, it turned out that he was indeed working on a project in the far outback of Queensland to study an unusual and rare raptor, the letter-winged kite (LWK).

So in July I found myself packed into a Range Rover 4 wheel drive with Jack and a student assistant Trish driving westward from Brisbane about 1000 miles into the Queensland outback. The unique aspect of the LWK is that it is the only hawk that hunts at night. But unlike owls, it uses vision, not audition, to find its prey. Ostensibly, we were testing the hypothesis that if the kite hunted by vision, then its success in hunting should be correlated to the phases of the moon. But in practice, we were just out there to study the biology of the kite and have some fun in a unique environment.

The environment

Most of the Australian outback is remote, flat, and desert-like. The northern tropical areas have two distinct seasons: a wet season and a dry season. In the more temperate southern regions, it is semi-arid where it is common to have a wet year followed by a number of dry years. During the wet years the grasses are abundant and the rivers and waterholes fill up. In the area that we studied in the Channel Country of the Queensland outback in the watershed of the Diamantina River, the abundance of grass is accompanied by explosive growth of the long-haired rat which feeds on the grass and is the main prey for the LWK. Unsurprisingly, with the surge in the rat population, the kite shows a corresponding exponential growth.

In 1991 we were in the Queensland outback following a wet year so the grass was beginning to die off but the rat and kite populations were still very high. The study area was actually within the bounds of a gigantic cattle ranch, the Davenport Downs Station, which was about 8000 square miles or 2/3 of the size of Rhode Island, the smallest state in the US. At the time they had about 10-15,000 head of cattle which they patrolled by plane and helicopter, as well on horseback. The towns we passed through on the way to the study site (Quilpie, Windorah, Charleville) are famous old outposts with a storied history in the outback. They have all seen better days though.

One evening while we were driving from one camp to another, we had a flat tire only to discover that the rental car did not have a lug wrench so we couldn’t change the tire. Fortunately we had a radio that could call the ranch for help so we pitched camp for the night and waited for help in the morning. The person from the ranch who came out to help us said that flat tires are a way of life out here in the heat: during one hot spell he changed 21 tires in 3 days! It was a bit of an embarrassment to have to call for help, as the Australian ethos of the outback is that you need to be prepared for anything. You should carry 2 spare tires just in case. Every summer there are stories of underprepared tourists getting stuck in the blazing outback and perishing before help can arrive.

One of the major ‘highways’ on the ranch

Coolibah trees line the small streams that provide water for the cattle

Lunchtime on the plains with Jack and Trish. Not seen are the numerous flies that swarm around your face which makes eating difficult.

Flat tires are common in the outback but our rental car was missing a lug wrench so we had to make camp for the night while waiting for help.

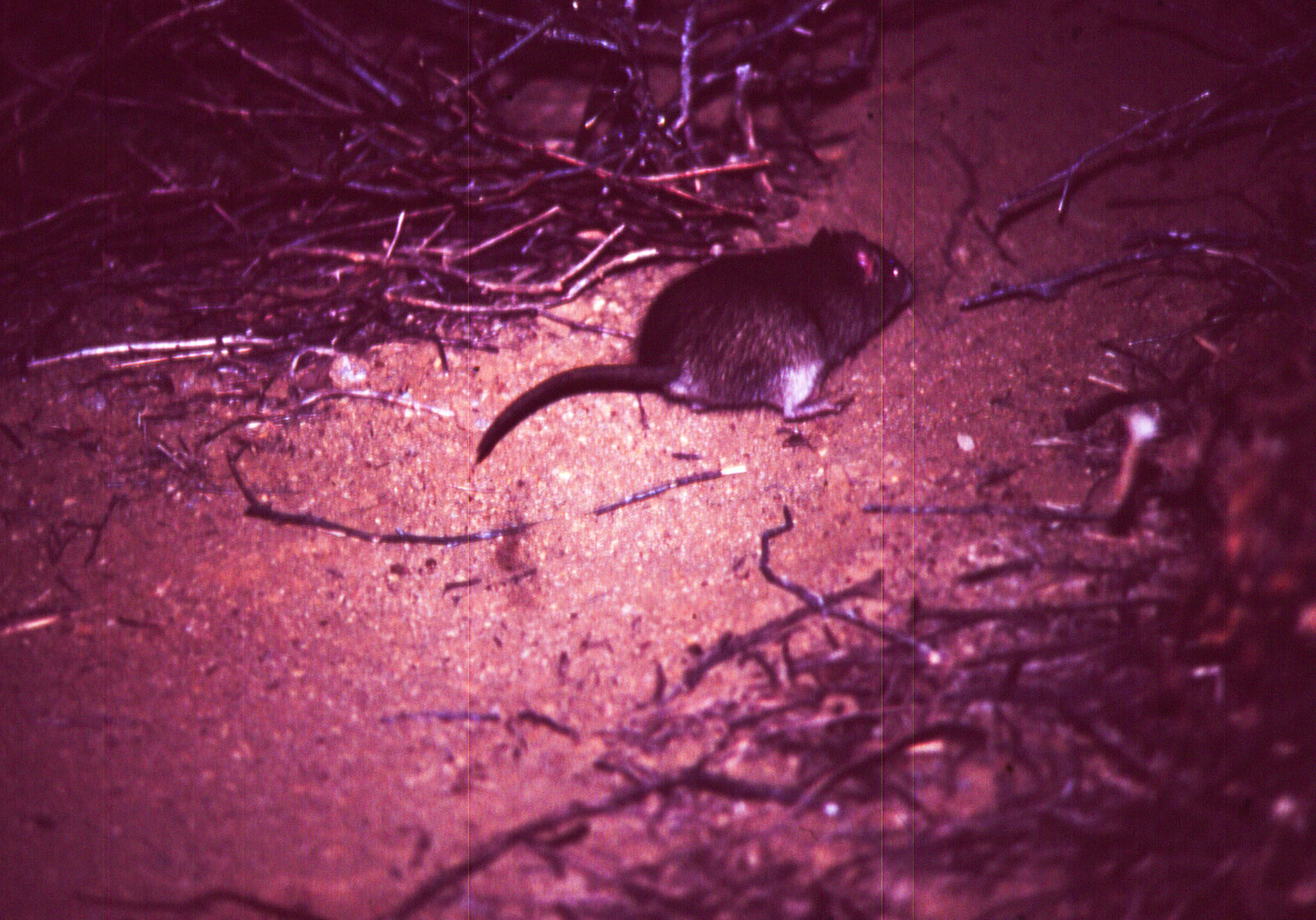

The prey: the long haired rat (Rattus villosissimus)

The main prey of the kites, indeed the only one, is the long haired rat, reputed to have been brought over from Europe on ships, though some claim it to be native to Australia. They are also known as plague rats for their ability to reproduce at a prodigious rate when the conditions are ripe, such as during a wet season. During such irruptions they are thought to be able to produce 12 young every 3 weeks. When present in plague proportions, it is no surprise to find that their primary predators, the LWK also irrupts in number.

The rats are famous in the Australian outback lore for having played critical roles in the iconic expedition of Burke and Wills, who famously died trying to cross the outback from Melbourne in the south to the Gulf of Carpenteria in the north in 1860-1861. In their journal, they described Cooper’s Creek as a lush waterhole, rich in fish and wildlife but at night the rats attacked and forced the explorers to set up a new camp. Later in the expedition when exhausted and dying of hunger, the men refused to eat the rat since civilized people did not feast on such game.

Most of the study area is flat grassland in all directions as far as the eye can see. The landscape is broken by an occasional small stream, along the banks of which are coolibah trees where the LWKs nest. As one walks out in the plains, about every third step you fall into a rat hole which riddle the earth. During the day the rats are underground to escape the heat but at night they come out in droves. We were camping out on the plains in tents and cooking at a campfire. As the sun set and the sky darkened, while sitting at the campfire you could begin to hear rustling in the grass as the rats began to wander out. If you let them, they would come up and nibble on your shoes or whatever was available. Fortunately nylon tents seemed to be too strong for them to chew on, though I’m sure they tried.

Rat holes dominate the landscape

The plains are pock-marked with rat holes where they spend their days to avoid the heat

A typical rat highway

As Burke and Wills described, after the sun sets, the rats take over.

Checking out what’s for dinner tonight

Close-up view of a rat with strobe light

A motion detector with a strobe is a good way to catch the rats scurrying about at night.

The predator - the letter-winged kite (Elanus scriptus)

The LWK is a rare raptor only found in Australia, chiefly in the outback. It is named for its distinctive underwing pattern that looks like an M, or W. They are often seen hovering in the air so the pattern is easy to see. For a raptor, it is relatively small. Of the world’s 290 odd species of hawks, eagles and falcons, it is only one that is completely nocturnal and it is thought that it hunts by vision, not by audition. Its eyes are larger than those of its relative, the diurnal black shouldered kite, but not markedly so. Up close its red eyes with prominent black rings are striking. It is relatively rare since it is usually only seen in the outback and is presently listed as near threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Since I was there in 1991, there are several reports that it has become very endangered with the advent of serious climate change.

The LWK is well-adapted to prey on the rats in the outback as it hunts at night when they are out. It is described as irruptive since its population soars when the rats are in plague proportions. During the day the LWKs hang out on the branches of the coolibah trees where they also build their nests. When you approach such a tree, the kites burst out like fireworks to fill the sky.

The M or W pattern under their wing is easily visible when they hover overhead.

LWKs gathered on a coolibah tree during the daytime. A nest is also visible on this tree.

Kites taking off as we approach the tree

Kites fill the air

The dark red eye is distinctive.

A handsome bird

Unusual flutter-flight with chattering appears to be a pair-bonding behavior that sometimes precedes mating

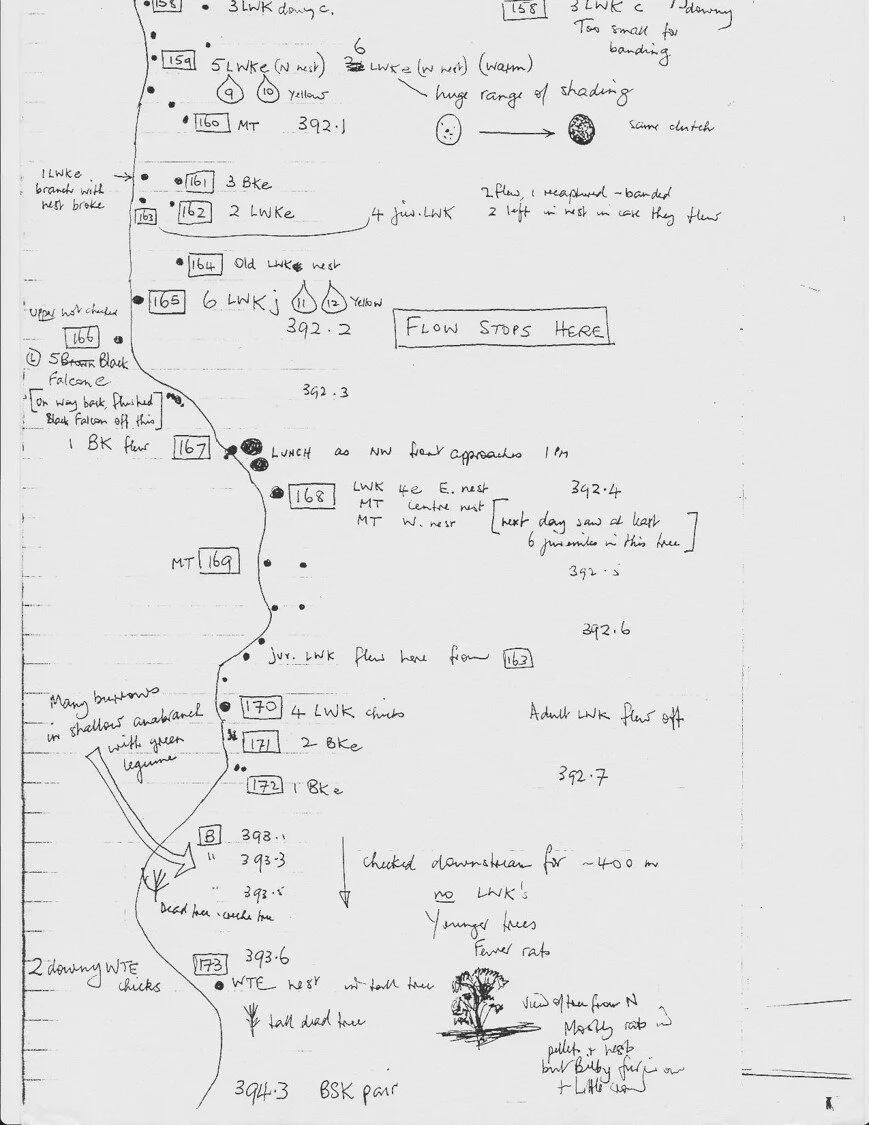

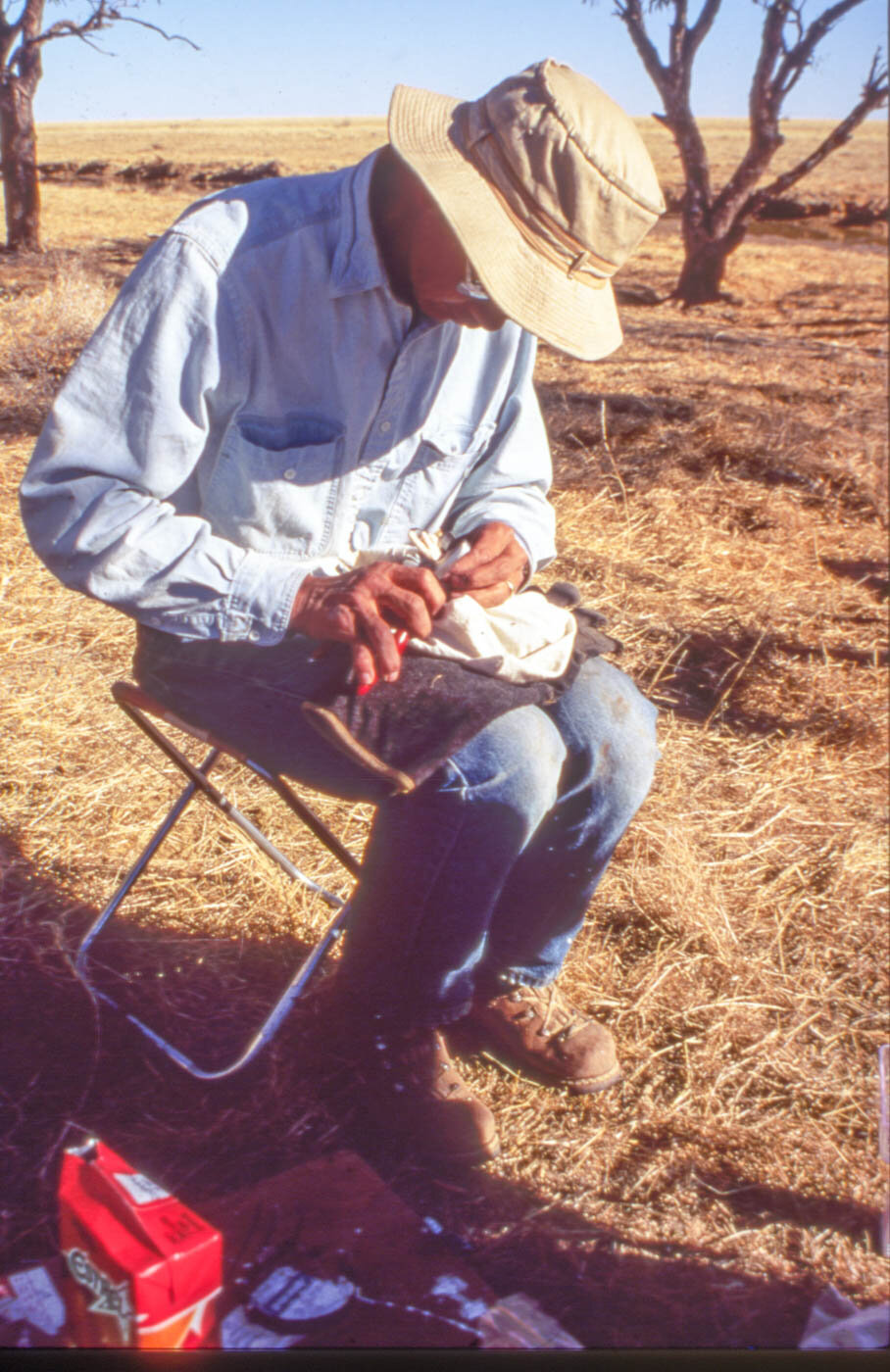

The science: counting, banding, tagging

This was the fourth or fifth trip for Jack to come to this study site. On previous trips he had mapped out the general layout of the stream with notes on all of the trees that had LWK nests. So we had data on which nests had previously had chicks. Furthermore, there were a number of birds that had previously been banded, either on the wing or on the leg. So we looked for banded birds and noted whether they were near their last sighting. During the day we spent most of the time checking each of the trees with nests to see if there were chicks, count them, and put bands on them when we could. In some cases we could peer into the nest by using a mirror mounted on a long pole, or even standing on the top of the car. However, usually some tree climbing was necessary to access the nest. Luckily the coolibah trees are relatively easy to climb as there are plenty of strong branches.

In addition to the hazards of climbing trees, the constant swarm of flies and biting ants could make life miserable, especially when they attacked while you were holding onto a branch with one hand and wrestling with a LWK chick with the other. Since we were there in the winter, the weather was pleasant and not stifling. In the summer Charles Sturt’s famous expedition into the outback recorded temperatures of 157 deg F in the sun and 130 deg in the shade, though these measurements might be apochryphal.

A sample page of Jack’s journal showing part of the study site with all of the coolibah trees that had nests marked.

A mirror mounted on a long rod was used to look into the nest from the ground.

Sometimes it was easy to access nests from the roof of the 4 WD.

Usually some climbing was necessary.

Luckily I liked to climb trees when I was young.

Jack is returning a banded chick in the canvas bag to the nest. Sometimes some additional support was needed for the thinner branches. Note the parent hovering overhead.

Oftentimes it feels rather precarious.

I’m high up in a tree but at least here not on a thin branch hanging far out laterally.

Trish also gets a turn climbing.

The cattle wander over to see what is going on while the parent complains from above.

Sometimes you need a little help from friends.

Banding young chicks under the shade of a coolibah tree.

LWK with a wing and a leg band. This juvenile kite is being released but it doesn’t realize it is free yet.

LWK being released after banding.

Eggs in the nest

Young LWK chicks

These chicks have the juvenile plummage but are still too young to fledge

Photographing diving LWKs

When the nests had chicks or eggs, the parents would be loudly protesting while hovering overhead as can be seen in many of the photos. Sometimes one of the parents got very agitated and would dive at high speed, or stoop, at the trespassers. I always made it a point to wear a hat for possible protection. Jack claimed that there has never been a case where the LWK would draw blood but they did sometimes dive with talons out. I wanted to get a good photo of a diving LWK but it is very difficult to hold still and not flinch while the kite is stooping straight at you at over 100 mph. Since the person actually at the nest was usually shielded by leaves and other branches, the subject of their stoops were usually the other people out in the open, like photographers.

LWK diving at the photographer

Hawks can dive at more than 100 mph!

Hovering with talons out ready to strike but since this is during the day when no rats are out, so there’s nothing to strike …except the intruders.

Night work

Since all of the action for the LWKs takes place at night, it makes sense to try to take some photos after the sun sets. We set up a camera on a tripod set on the roof of the jeep to get more height and set up a strobe light with remote release of the camera and flash. We aimed the camera at a likely nest with hungry chicks and active parents.

Like many raptors both parents are engaged in hunting for and feeding the young. Often, the female stayed at the nest while the male went to get rats. As you can see from the photos, the parents were kept busy all night bringing rats home to the nest.

Camera set up on a tripod on the jeep and aimed at a likely nest with strobe lights.

Bringing home the bacon

Here the female is on the nest as the male brings a rat home

As mentioned above, our principal aim was to test the hypothesis that the success of hunting rats was correlated to the phases of the moon, with higher success rates at full moon. There were preliminary observations that this was true, mainly from early field observations that there was blood on the talons following moonlit nights but not at new moon. But no one had ever tried to measure this directly.

We attacked this question by trying to monitor a single nest with binoculars throughout the night and count the number of rats brought in. We were there during a time when the moon was waxing so it became gradually lighter during the latter phase of the trip. Our data supported the hypothesis, i.e. there were more successful captures when the moon was brighter. However, I pointed out to Jack that when the moon was not out, it was nearly impossible for me, at least, to tell whether the LWK returning to the nest had a rat or not. As you can imagine, this is exhaustive work to try to remain alert and awake peering through the darkness all night, while working all day as well. So, we were only able to do the night measurements on a few occasions.

Other animals

Of course with rats so plentiful, LWKs were not the only animals around. Several other predators of the rats also thrived during the rat irruptions.

Inland Taipan snake (Oxyuranus microlepidotus)

Australia is famous for having many of the most venomous snakes in the world. The inland taipan snake is a denizen of the Queensland outback and its venom is by far the most toxic in the world. The venom from a single bite from this snake can reputedly kill 100 grown men. Left untreated, a single bite can kill a man in 30 minutes. Fortunately for us, the snake is rather reclusive and not very aggressive. Furthermore there was plenty of food for them. So although we saw a number of them, most avoided us and we certainly did our best to avoid them except when taking a photo. Since the snake is only out during the day when the rats are underground, it must search for them in their burrows or wait until twilight for them to appear.

Searching for a rat.

Barn owl (Tyto alba)

Unlike the inland taipan snake which is only found in the Australian outback, the barn owl is widely distributed throughout the world. It is specialized to hunt small mammals at night so the irruption of long haired rats in the outback is ideal for it. We often saw barn owls hanging around during the day and even came across a nest of three barn owl chicks in a hollow tree. Unlike the LWKs, the barn owls hunt the rats using audition.

Wedge-tail eagles

Soaring wedge-tail eagle

Another fairly common raptor that we saw were wedge-tailed eagles. Like the taipan snakes they had to rely on hunting the rats at dawn or dusk as they are not prepared to hunt in the darkness.

Wedge-tail eaglets in a nest

Juvenile wedge-tailed eagle

Other notable wildlife

In my notes I mention also seeing many kangaroos, emus, wild pigs, black and brown falcons, parrots, brolgas, galahs and bustard birds but without any good photos.

Bilbies (or rabbit-eared bandicoot) are a rare marsupial once thought to be extinct but now classified as highly endangered. I think most native Ozzies have never seen one in the wild as they are also nocturnal and shy.

Black kites were also common

Goannas are a common sight in the outback

Goanna

A flock of pelicans

Brolgas

Feral cats are a huge problem in the outback as they are decimating the native wildlife.

Of course there is the ubiquitous dingo

Sunset on the Diamantina

Epilogue

On May 7, 2019 Jack Pettigrew passed away in a tragic automobile accident in Tasmania. He had been working on a book of his studies of the LWK though, to my knowledge, only a few chapters had been written. When he stayed with us in Madison for 6 months a few years after my sabbatical, it was clear that his interests had moved onto other questions. Now with his death, it seemed unlikely that the story would ever be published so I began to scan and digitize the slides that we had taken. I’ve co-opted his projected title for the book for this blog. A few of the photos were taken by Jack in earlier trips to the study site. This blog is dedicated to Jack’s memory.

Please note: All text and photos are copyrighted to Tom Yin. You are welcome to share the URL, however re-production of text or photos is not permitted. If you would like to feature this story, contact me and I would be happy to provide you with details, photos, text etc. Thanks!